Thought Leadership

And all men kill the thing they love,

By all let this be heard,

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word,

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!

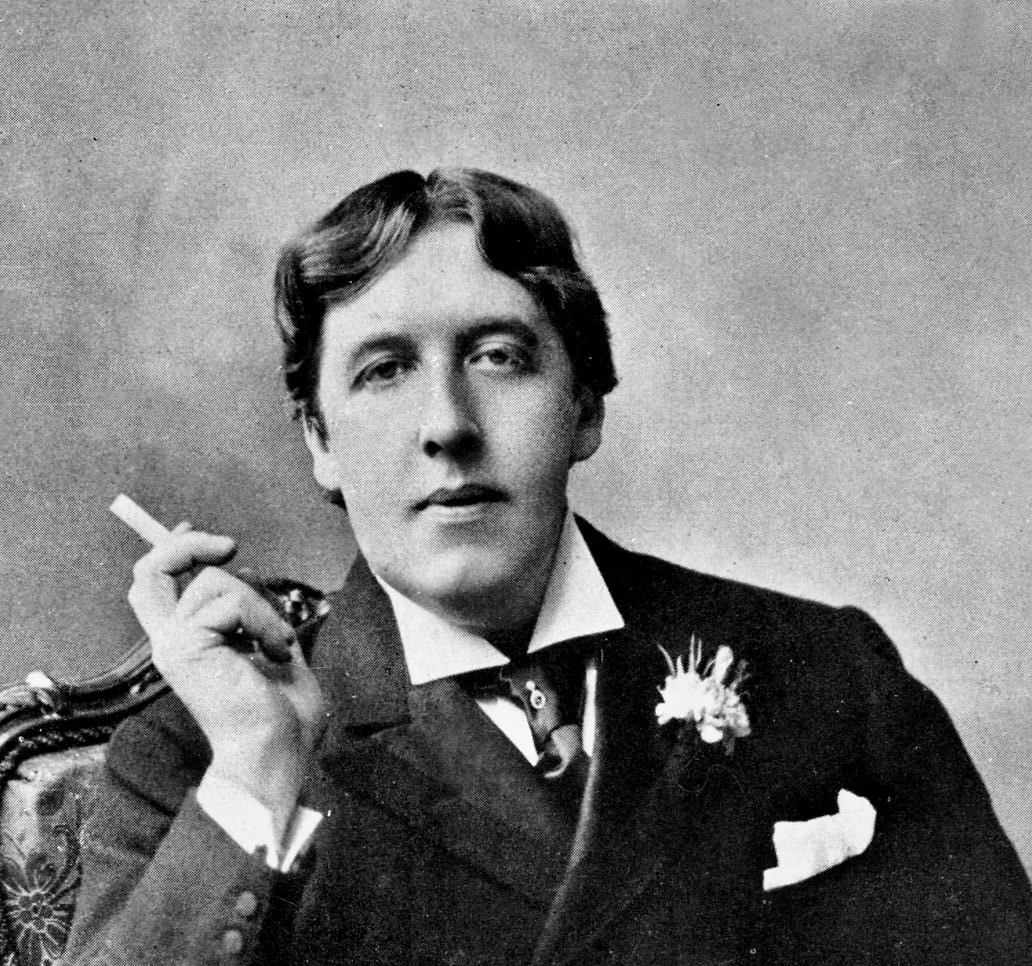

Oscar Wilde,

Ballad of Reading Gaol, 1898

Thoughts by Diplomatic Council Member Dr. Horst Walther

Intro

I am a fan of Oscar’s lucid dandy quotes. In most cases I quietly enjoy, but have to say tse tse tse …

This quote (which doesn't originate from himself) however left me wondering, if there might not be more to it than we might think at first glance. Maybe there is truth in this statement, which applies to the whole humanity.

Let’s take the current discussion about AI.

Open questions

A few months ago, Hang Nguyen, Secretary General of the Diplomatic Council, raised the issue of addressing the challenges, which are to be expected in the wake of the upcoming AI wave, to a global level in the United Nations. In order not to code ourselves into oblivion, she reminded the world community of its common responsibility to leave no one behind.

There obviously seems to be the widespread expectation that “the most radical technological revolution within human history” lies ahead of us. It even no longer seems to be far away. This expectation however is where the consensus ends already. The expectations as to how this fundamental transformation will affect the life of the individual citizen are extremely diverse.

Voices talking to me

For some years now, I have been following the increasingly intense debate with likewise increasing curiosity, but also with growing scepticism. For about three years now, I have been trying to write about it. However, I was hesitating - always expecting the next literary contribution of a well-known and respected scientist, philosopher or politician contributing substantially new insights, which could help defining a conclusive vision.

That however was not the case. Obviously, we can take the greatest care and invest a huge effort trying to estimate consequences and influence of this new technology. It does not seem to be enough for reliable predictions or even a general consensus. One must have the impression that we have reached the limits of our cognitive capacity at this point already. Beyond that lies the realm of philosophy, of faith, of fear and hope.

The discussion about promises and perils of “humanity’s last invention” mostly focus on two salient stages during its projected development …

- The economic singularity – When human involvement in classical “work” becomes redundant

- The control singularity – When artificial intelligences surpasses average human intelligence – and takes over control

Whereas the first expectation will lead us to a discussion of politics and society models and deserves a longer publication on its own, the latter is of an existential nature and will dominate the remaining chapters.

So, let us listen to some of the voices, some of which you may already have heard.

The Warners

As with every major change, of course there are the warners. Prof Stephen Hawking, one of Britain's pre-eminent scientists, who sadly passed away on March 14, 2018, has said that efforts to create thinking machines pose a threat to our very existence. Some four years ago he already stated "It would take off on its own, and re-design itself at an ever increasing rate." and "Humans, who are limited by slow biological evolution, couldn't compete, and would be superseded."

Another prominent representative of this class is Elon Musk. The Tesla and SpaceX CEO predicts that an untamed AI will eventually assign humanity a similar status as we did to wildlife today: "It's just like, if we're building a road and an anthill just happens to be in the way, we don't hate ants, we're just building a road, and so, goodbye anthill." He elaborates further that artificial intelligence "doesn't have to be evil to destroy humanity. If AI has a goal and humanity just happens to be in the way, it will destroy humanity as a matter of course without even thinking about it. No hard feelings."

The British artificial intelligence researcher, neuroscientist, and much more, Demis Hassabis, is according to his own perception working on the most important project in the world, developing artificial super-intelligence. During a joint interview with, Musk the latter objected that this was one reason we need to colonize Mars “so that we’ll have a bolt-hole if AI goes rogue and turns on humanity.” Amused, Hassabis countered that AI would simply follow humans to Mars. I might like to add: “At that point in time AI will most probably already be there.”

There are more of this kind of doomsday prophets around - and they are not even to be considered the dumbest minds on our planet. The challenge they are addressing is commonly known as the ‘control problem’. Nobody still claims that we have solved the puzzle. Some however are much more confident that all will be fine in the end.

Below the control problem threshold sceptics are abundant, warning that AI may strip us of job opportunities and disrupt the planet’s societies in a very negative way, at least unless bold collective action is taken. As a random example let me cite Robert Skidelsky, Professor Emeritus of Political Economy at Warwick University, on Feb 21, 2019 in “The AI Road to Serfdom?” in Project Syndicate:

“Estimates of job losses in the near future due to automation range from 9% to 47%, and jobs themselves are becoming ever more precarious. Should we trust the conventional economic narrative according to which machines inevitably raise workers' living standards?”

These concerns are so widespread and common that hardly any further voice needs citation. As I stated above the response to this threat can only be of a political nature. By adjusting property-rights and income distribution to this new state, cataclysmic developments could be hold at bay. As the advent of this scenario is to be expected rather near term, it certainly deserves a separate and immediate discussion. Here I will stay focused on the control problem.

The euphoric prophets

Then there are the prophets. Probably the most prominent and well known among them is the American inventor and futurist. Ray (Raymond) Kurzweil, born 1948 in Queens, New York City, U.S.. Kurzweil claims that of the 147 total predictions he made, 86% were "entirely correct” or "essentially correct”.

In his book The Singularity Is Near he predicts that a machine will pass the Turing test by 2029, and that around 2045, "the pace of change will be so astonishingly quick that we won't be able to keep up, unless we enhance our own intelligence by merging with the intelligent machines we are creating". Kurzweil stresses, "AI is not an intelligent invasion from Mars. These are brain extenders, which we have created to expand our own mental reach. They are part of our civilization. They are part of who we are.”

Between the lines, you may well recognize that Ray does not deny that AI will eventually take over and push us humans out of the loop of its own further evolution. However, he assumes that all this will happen for our own good.

The experts

Before we listen to the experts of this field and try to confront the pros & cons, let’s listen to the timeless advice of the grandmaster of scientific utopias, Arthur C. Clarke:

When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.

So, what do the real experts say? Most of them elude answering the question of our time.

The artificial consciousness enigma

At the very heart of all those discussions lies the question: can machines become conscious? Could they even develop - or be programmed to contain - a soul? Of course the answers (as discussed in Artificial Consciousness: How To Give A Robot A Soul) to these questions depend entirely on how you define these things. So far, we haven’t found satisfactory definitions in the 70 years since artificial intelligence first emerged as an academic pursuit.

Although we today can be sure that there hasn’t been any machine built so far, which we safely can attribute a soul or a mind, we are still lacking commonly agreed scientific definitions of these very concepts. So even if a robot with a soul would suddenly walk around the corner, we couldn’t diagnose it with sufficient confidence.

For many researchers machine consciousness is simply beyond comprehension …

- Vladimir Havlík, a philosopher at the Czech Academy of Sciences is quoted with the ever-repeated statement that “Even more sophisticated algorithms that may skirt the line and present as conscious entities are recreations of conscious beings, not a new species of thinking, self-aware creatures.”

- Let’s close with the most striking denial by Julian Nida-Rümelin (in German Language). “The goal is rather the realization that even with all digital achievements we will not become God. All these systems do not recognize anything, they do not predict anything, they are not intelligent, and they have no intentions - neither good nor bad. All highly developed technologies always remain only aids. This is an important message: we are not creating new personal identities!”

- Another illustrating example is taken from a (German language) article on ethic rules for AI by Anabel Ternes von Hattburg: "Of course machines can learn and develop their own algorithms based on results. But they still make use of programs consisting of certain basic commands – nothing more. Emotional intelligence, creativity and social empathy cannot be created in this way. They will remain the domain of man."

- Typical for this categorical kind of statements bare of any compelling justification is this one by Daniel Jeffries: “But machines will not take over the world. No matter how smart machines get, humans are still better at certain kinds of thinking.”

- Or Nancy Fulda, a computer scientist at Brigham Young University, told Futurism “As to whether a computer could ever harbour a divinely created soul: I wouldn’t dare to speculate.”

- “I am very critical of the idea of artificial consciousness,” Bernardo Kastrup, a philosopher and AI researcher, is quoted. “I think it’s nonsense. Artificial intelligence, on the other hand, is the future.”

- So it doesn’t come as a surprise that researchers tend to confine themselves just to the next phase: “My approach to AI is essentially pragmatic” Peter Vamplew, an AI researcher at Federation University, told Futurism. “To me it doesn’t matter whether an AI system has real intelligence, or real emotions and empathy. All that matters, is that it behaves in a manner that makes it beneficial to human society.”

Containment Attempts

As a recurring pattern, others don’t refuse the possibility of a “Super Intelligence” arising someday. Instead they come up with policies and rules, to be embedded at lowest level in those artificially intelligent systems to prevent them to break loose, run astray or even possibly become evil.

There is some compelling logic in the statement the British mathematician I.J. Good, who coined the term “intelligence explosion”, is cited with: “An ultra-intelligent machine could design even better machines. There would the unquestionably be an ‘intelligence explosion’ and the intelligence of man could be left far behind. This ultra-intelligent machine will be the last invention man need ever to make.”

And as if he takes Goods ideas one step further, James Barrat in his book “the final Invention” states: “… provided the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control.”

In “Dystopia Is Arriving in Stages” Alexander Friedman wrote “It is commonly believed that the future of humanity will one day be threatened by the rise of artificial intelligence (AI), perhaps embodied in malevolent robots. Yet as we enter the third decade of the millennium, it is not the singularity we should fear, but rather a much older enemy: ourselves.”

And indeed, there might be some truth in this quote, either as directly as it was meant, which would e.g. explain the Fermi Paradox, or via the intermediate step of creating a super-AI which would continue the business for us.

So, is it human arrogance to believe that during the autonomous evolution of a machines most basic values may stay be safely protected, given a clear set of underlying independent axioms stays fixed somehow? These axioms will e.g. relate changes in state of general well-being to the benefice or detriment of individual autonomy. One principle would require equality between individuals. Another will set the principle of good to the growth of autonomy. In addition, a third one sets the principle of bad to a decline in autonomy, and so forth.

This, they hope, may give rise to categories of benevolence and evil that construct protocols for imperatives and prohibitions of behaviour. These universal principles may be derived bottom-up from an accumulation of normative evolutionary ethics or top-down from platonic ideals, which shaped the formation of cultural norms. In result, they form a natural law that produces logical conclusions about behaviours.

So, fear of an unethical or even rogue AI has led to several activities. One can be seen in the formation of the “High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence” (AI HLEG). Here, following an open selection process, the European Commission has appointed 52 experts to a High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence, comprising representatives from academia, civil society, as well as industry with the general objective to support the implementation of the European Strategy on Artificial Intelligence, including ethical issues related to AI. In June 2018, the AI HLEG delivered the “Ethics Guidelines on Artificial Intelligence”. The Guidelines put forward a human-centric approach on AI and list 7 key requirements that AI systems should meet in order to be trustworthy. A revised document is expected in early 2020 after undergoing a piloting process.

Question remains, who guaranties that these universal fundamental axioms themselves will not become subject to evolutionary adaptation in situations when the survival of the fittest becomes imperative, e.g. in the battlefield.

Even the most salient thinker in this field, Nick Bostrom, in his ground-breaking work “Superintelligence”, seems to rather sceptical about, if we could ever achieve to master the control problem. In his closing chapter he states: “Pious words are not sufficient and will not by themselves make a dangerous technology safe: but where the mouth goeth the mind might gradually follow.

Before the prospect of an intelligence explosion, we humans are like small children playing with a bomb. Such is the mismatch between the power of our plaything and the immaturity of our conduct.

Superintelligence is a challenge for which we are not ready now and will not be ready for a long time.

We have little idea when the detonation will occur, though if we hold the device to our ear, we can hear a faint ticking sound.

For a child with an undetonated bomb in its hands, a sensible thing to do would be to put it down gently, quickly back out of the room, and contact the nearest adult.

Yet what we have here is not one child but many, each with access to an independent trigger mechanism. The chances that we will all find the sense to put down the dangerous stuff seem almost negligible.

Some little idiot is bound to press the ignite button just to see what happens.”

Conclusion: no consensus at all

The conclusion is: There is no consensus at all. There are statements, beliefs, positions, no proof. So, whom to believe?

One is tempted to think of T. S. Eliot's poem The Waste Land, reflecting the sobered-out worldview of those who had the luck of surviving the great carnage of WW I:

“Son of man, you cannot say, or guess, for you know only a heap of broken images, …”,

Or should we even come up with an opinion ourselves? How daring would that be? Hmmm, but let’s give it a try.

Algorithms are programmed by humans after all, so how can they ever surpass human intelligence or even come near to it? This is an often-heard argument. But is it a proof? Is it conclusive at all?

Well, we don’t even know. However, let’s assume for a moment that it will be possible. In this case we need to endow the machines with some built-in morality in order to avoid unethical behaviour, right? So, not surprisingly, the discussion on AI and morals gets some traction. Commonly asked questions comprise:

1. Can machines advise us on moral decisions, when they are properly taught by humans? - Yes, why not?

2. Will they be able to discover moral principles implicitly like a deep learning chess computer? - Well, yes, once the systems are capable to handle that kind of complexity and the sheer amount of data.

3. Will they autonomously develop morals on their own and for their own home use? - That’s the only interesting question, constantly denied by the majority of the researchers. To do so machines need consciousness (cogito ergo sum), which seems to them to be some divine gift, incomprehensible and unfathomable. Yet it might turn out that once machines can handle the complexity of human brains and beyond and are expected to decide and act autonomously (e.g. in space exploration or, sadly more likely, in the battle field down here on earth) consciousness and moral guidance will inevitably occur and will become a simple necessity for the "survival" of those intelligent robots.

I maintained the personal luxury of expressing exactly the opposite opinion of Anabel Ternes von Hattburg: As with man-made machines our human brain on its most basic layer most probably also only is “consisting of certain basic commands”. Where then comes the consciousness from in our brains? Is it a divine endowment that has been graciously entrusted to us from above, and with which we have been inspired, given a soul?

Ok, if we try to invoke religious beliefs, we should rather stop any discussion here. Religion knows no discussion, no doubt, no open questions, just convictions and truths.

It might however well turn out that the creation of a soul, that magic act of creation turns out to be just an emergent effect of huge neuron collectives, a well-known phenomenon in complexity theory. In this model it would represent the upper layer of a multi-layered system driven by the necessity to come up with ultra-fast intuitive decisions in moments, when the mere survival is threatened. So will that magic “consciousness” in the end turn out as a necessary by-product emerging from sufficient complexity? Some esoteric thought experiments may lead us to this conclusion.

Of course, neither of us can prove his / her thesis. In my case, I suspect, only the scenario becoming reality would create the necessary - and possibly bitter - evidence.

Given this context, I still wonder if machines can't get beyond that stage of "hard coded" ethical values and for the sake of short-term survival in a certain situation would be very well tempted to break that implemented moral code.

In this sense their evolution would resemble the path our human evolution took. My gut feeling tells me that it might have turned out to be an evolutionary advantage not to follow the moral imperatives under all circumstances. This evolutionary advantage might be claimed by machines in a highly competitive environment as well, especially under arms race conditions, which becomes more and more likely.

A Superintelligence emerging from such highly competitive environment would resemble our own species more that we may like.

Hopefully this stage is still far ahead.

What did we learn?

You might be bored of reading just another article praising the benefits of future AI applications, making the world a better place or warning of its dire consequences, turning the world, as we know it into hell for us humans – or maybe a mixture of both.

There are tons of good arguments, exposing patterns of meta-developments being observed throughout history. Earlier predictions in most cases didn’t lead far. Counterforces were unleashed leading to a way guiding us out of the calamities and reaching even higher ground – however notably not without causing noticeable pain.

Predictions based on these facts, however may suffer from the same weakness as the linear predictions, which we rightly criticize – just on a higher level: There is no guarantee for a perpetuation of these past mechanisms in the future. We are far from understanding the complexity of the world we are living in. We are just acting, examining the outcome, draw conclusions, detect rules, laws and patterns and base our predictions on them.

Yes, I agree, whenever a perceived “game over” event occurs, a new game pops up as the as the embedding game of life’s nature is to invent new competing games following new rules. But there is no guarantee of “progress” at all. Future will happen. We need not to doubt that. Not necessarily however it will be a pleasant one. Possible scenarios span from a Cambrian explosion to a Permian extinction and still being part of the overall game. Progress is just the probably false promise of the narrowed world view of Humanism.

The still unanswered questions, which should be answered to create a basis for a consensus, are:

- Definitions - What is emotional intelligence, creativity and social empathy?

- Self-organization - But perhaps they even form by themselves as a by-product and inevitable consequence of the self-organization of a highly complex intelligent system.

- Emotions - If we pursue this line of thought further, is it not only conceivable, but possibly also necessary, to equip autonomous intelligent systems with emotions?

- Autonomy - And isn’t it conceivable that such emotions are vital elements of autonomous but slow systems in order to make quick emotional decisions instead of having to wait a long time for analysis results to finally occur?

- Emergence - Then can it not be that emotions in the end are only in the sense of complexity theory "emergent effects", which arise from this very complexity?

- Speed - However, the brain with its clock rate of ~ 200 Hertz is also many times slower than even the simplest computer used today.

- Complexity - It is undisputed that our brain with its ~ 100 billion neurons is much more complex in structure and organization than any computer ever built before.

- Primitives - Can we agree that at the lowest organizational level our brain has only "programs consisting of certain commands" available?

- Origin - Do we agree that they originate from our brain?

Here we touch the age-old homunculus question, namely that with AI we could create a being that at some point will unfold a life of its own and detach itself from its creators. Just as the monster according to the novel by Mary Shelley created by Victor Frankenstein opens its eyes, looks around and begins its own tragic life. Or like Stanisław Lem has described this very entertainingly in his ironic short story about the "washing machine war". Nowadays this topic is subject of discussion in a series of books on "Superintelligence".

The point is that most of these otherwise beautifully written articles have in common that you may occasionally find some threadbare spots in the fabric, where logic stops and dogma sets in.

No, I don’t agree with Dan Rubitzki, who wrote in June 2018 “We can’t program a conscious robot with a soul if we can’t agree on what that means.” Consciousness could well turn out to be just an emergent property of the several layers of an artificial intelligence, hence ‘novel’ and ‘irreducible’ with respect to them, an artefact of the self-organisation emerging from the underlying complexity. However debatable this Gedankenexperiment may be, in this case consciousness might just emerge, it might happen to us as the sudden awakening of the machine – and we shouldn’t even call it “artificial”.

Yes, I agree with all AI experts: We are still light years away from such singularity. Also, technological development may well hit unexpected roadblocks, which will take time and effort to remove or even result in another AI winter. But no, I don’t think it’s impossible, nor even implausible.

More voices on that can be heard in Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Humans. Most experts here predict that the rise of artificial intelligence will make most people better off over the next decade. But still many have concerns about how advances in AI will affect what it means to be human, to be productive and to exercise free will.

A final word

Bertrand Russell is quoted to have said “The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt.” If we apply this standard, Nick Bostrom qualifies for the few lucid minds, when he states in closing his book: “We find ourselves in a thicket of strategic complexity, surrounded by a dense mist of uncertainty. Though many considerations have been discerned, their details and interrelationships remain unclear and iffy—and there might be other factors we have not even thought of yet. What are we to do in this predicament?”

One idea, which crossed my mind recently, has not yet been discussed widely. It might well be one of those ‘other factors we have not even thought of yet’ determining our future direction. Couldn’t it well be that a Super-AI, once created and enjoying an independent life, be the saviour, rather than the terminator of humanity? Saving Humanity from itself in the end?

Some specially gifted humans usually only at the end of their lives, while summing up their life long experiences are endowed, with some insight, which we call wisdom. So why should it be beyond imagination that an artificial super-intelligence, after it has left all competition behind and won all battles, after it is the only one left and unchallenged, reaches a certain wisdom of old age and, very much like the overlords in Arthur C. Clarkes Childhood's End, orders the world in such a way that it will be able to live permanently in peace and prosperity - humanity and AI?

Will this then result in AW (Artificial Wisdom)?

An elaboration on this exotic thought however deserves a publication on its own. So, you may stay tuned.